By Catherine DiMercurio

If you’ve been following this blog, you know I’ve been talking about transitions a lot lately. One kid is off at her first year of college. One kid has a freshly minted driver’s license, beginning his junior year of high school, and driving himself to school, work, cross country practice. I’m entering my fourth post-break-up month and watching how fast it’s all going by, imagining the day in the not-far-off future when I drop my son off at college and return to an empty house. It has been an angsty summer, and some of the freshness of fall has similarly been curdled by anxiety. So much is changing, so quickly. The children are strong, adaptable, but also not impervious the stress of these new circumstances either. As their mom, I long to make it easier somehow, but I know there’s nothing I can really do. The hardest part is, they know it.

Some days, I have the sense, that I’m close, that I’m on to something. I’ll turn a corner and gain a new understanding that allows me to put a difficult past into perspective, to synthesize. I’ll be able to embrace the new normal, stop caring what people think. Soon, I tell myself, I’ll be truly moving forward, not in this halting, breathless, slowpoke, dizzying way I’ve been doing. Soon, I’ll be one of those wise, forgiving women full of light and kind words, good humored, emotionally supple. I keep feeling that I’m close to having a transformative realization, an epiphany that allows me to step gracefully into the next phase.

Against Epiphanies: Lessons from Fiction

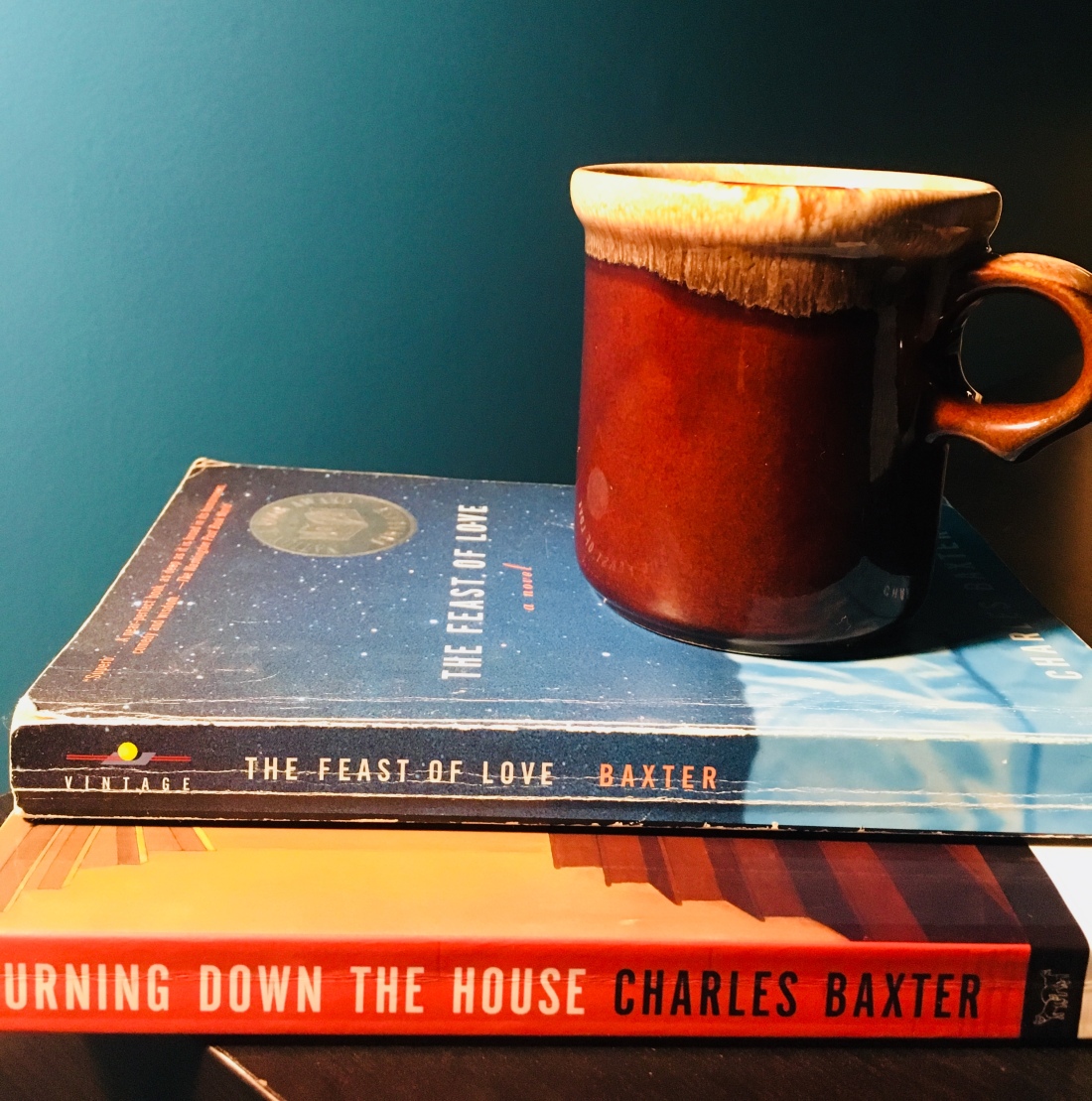

When I was in grad school I read a series of essays on writing by Charles Baxter, a favorite author of mine (please read his novel, The Feast of Love, if you haven’t, and please read it again if you have). One of the essays came to mind as I thought about this feeling of being within reach of something—an epiphany—that I could not quite grasp.

In “Against Epiphanies,” Baxter writes, “I can say with some certainty that most of my own large-scale insights have turned out to be completely false. They have arrived with a powerful, soul-altering force; and they have all been dead wrong.” I underlined this and wrote some questioning notes in the margins of this page, Baxter’s comments having ushered in a sense of discomfort I couldn’t pin down. Later, he goes on to say, “I must confess a prejudice here, which is probably already apparent. I don’t believe that a character’s experiences in a story have to be validated by a conclusive insight or a brilliant visionary stop-time moment. Stories can arrive somewhere interesting without claiming any wisdom or clarification, without, really, claiming much of anything beyond their wish to follow a train of interesting events to a conclusion.”

Sometimes Things Just Happen

I think this is one of the qualities I like most about reading Baxter’s fiction, the realness of the fact that life serves up precious few epiphanies. At the same time, I found it tough medicine to swallow as a writer. There is an urge to distill, to make meaning, to have everything lead somewhere. But sometimes, often, everything doesn’t lead somewhere, or even, anywhere. Perhaps, too, it is what I’m struggling with as a human. Experiences don’t necessarily lead us to brilliant conclusions, a life-altering insight: “it was then that I realized that everything had led me to this point.” Because what if it didn’t, it hadn’t? Does this leave us in some existential morass? Or do some experiences shape us, but not necessarily in an obvious, it-taught-me-a-lesson sort of way? Even though everything doesn’t lead us to something, we still have a journey, and we still find ourselves in various places along the way.

My son and I recently had a conversation about this very thing. We’d headed out to a local lake to do some kayaking on one of the few days we both didn’t have any other obligations. My daughter was already away at school. Some car trouble though threatened to end our fun before it began. In the end, we sorted through it and were still able to enjoy a little time on the water together. As we drove home, I wondered aloud what lesson I was supposed to learn from this. Maybe it was about resiliency or something. My son’s response to my line of questioning was, “Maybe it’s not a lesson. Maybe it’s just a thing that happened.”

Validation and the Role of Trauma

I think Baxter and my son were essentially saying the same thing—experiences don’t have to be validated by insight. At least not all of them. It’s not as if we never learn anything from our experiences. But an experience isn’t rendered valueless if we haven’t translated it into a discrete life lesson.

I think the tricky part is being able to tell the difference between when we do have something to learn, and understanding when an event is simply a thing that happened. When a person has been through a trauma, it can be difficult in the aftermath to not have every stressor feel exactly the same as the trauma itself. It takes a while before our stress response can calm down, before an argument with a loved one or a traffic jam that makes us late for work feel different from the worst parts of the trauma. Maybe being able to tell the difference between experiences from which we can draw meaningful insights and experiences that are simply happenings is a skill that takes time to develop, or an instinct we have to train ourselves to trust. I’m certain trauma plays dark tricks here too, making us believe that if we don’t learn something meaningful from every experience something bad will happen, again.

I’m certain trauma plays dark tricks here too, making us believe that if we don’t learn something meaningful from every experience something bad will happen, again.

I like insights. They are comforting. And they are important. But the big life-changing ones are few and far between, and maybe, like Baxter points out, they are often dead wrong. I wonder if the reason such powerful epiphanies turn out to be dead wrong is that we gave them so much power. We smother them with expectations. Perhaps accumulating smaller insights, making minute course corrections as we go without expecting them to change our lives is, in fact, how we change our lives. Perhaps the perspective we seek, or the life we’re after, will be achieved forty-seven small insights from now, rather than in one big epiphany.

Love, Cath

I think he’s right, you’re right. Things just happen. As much as we’d like for there to be hidden meanings in every little thing (why is that, by the way? Might have to ask someone taking an intro psych course…) – the “God must’ve wanted me to learn from this” mentality, or the “it must be Fate” frame of mind… Why? Why does everything have to be an experience? Can’t we just *Be*? Do those people think a higher power is actually so involved in their daily lives that *everything* is a lesson, epiphany, or life-affirming realization? I stubbed my toes the other day – I can either take away “watch out for the heavy cooler you already knew was there and ran into anyway” or I don’t have to take away anything. I smashed my toes in, it hurt, I swore, I moved on.

I wonder if the “epiphany of nothing” is a means to move on from the past for some. Maybe the realization that their days won’t be filled with earth-shattering realizations or hard-learned lessons is a way to move past all those and they can just breathe, live, and move on, taking comfort in the “things sometimes *just happen*”.

Sorry for all the *words*. I don’t have an italics option!

LikeLike